No other portion of a ballfield construction or renovation project has more impact on the success of your facility than the finish grade and the resulting surface drainage pattern. Water percolates very slowly through native soil fields and on infield skin areas. Positive surface drainage is the fastest way to drain these areas. Only a sand-based field can meet or exceed the speed of water moving off a field by surface drainage. When properly designed and graded, positive surface drainage can speed availability of fields after a rain and make field prep a breeze.

Find the right contractor

Always hire an experienced and qualified sports field contractor who will use the correct equipment to get your expected results. Make sure they:

- Have a portfolio of installations/renovations from the last two to three years of natural baseball/softball surfaces, and a list of references.

- Work with conical and/or single/dual slope laser-guided grading equipment to achieve the appropriate grade.

- Ensure proper and full incorporation of any material added.

- Add or remove material as needed in order to meet specified grade.

- Achieve finish grade tolerances of plus or minus ¼” or better, and allow confirmation before moving to next step.

Finish grade recommendations

Grading new construction ballfields is usually easier because you are starting with a clean slate over the entire field. When renovating an existing field, the challenge greatly increases. You will likely have to merge with existing grades at some point. Never grade a ballfield so that it is perfectly flat. All fields — even the best-draining sand-based fields — should have some slope to move water across the surface, especially after heavy rains. The following recommendations are applicable for fully skinned or grassed infields. Recommended slope will depend on whether a field is native soil or sand based, the level of play, and the drainage pattern chosen.

0.5%: Sand-based fields — professional level and high-end college ballfields

0.5% – 1.0%: Native soil fields — college, high school and recreational ballfields

Grading and drainage patterns

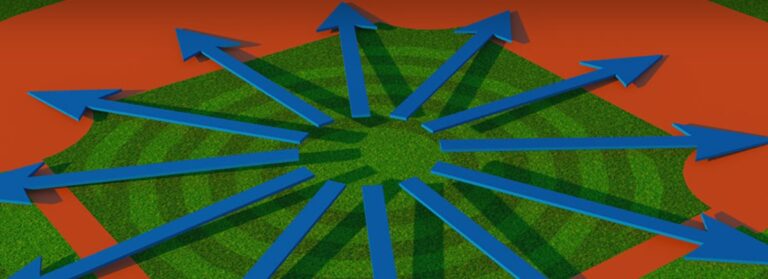

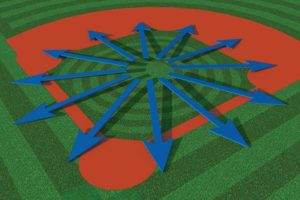

Conical design

This is the “Cadillac” of surface grading/drainage for infields. With this design, water moves off the infield in the shortest travel distance possible. The conical design is performed using a cone laser set up on the mound and projecting a cone shape over the field to guide the grading. With the conical design, once water has entered the outfield, it must travel the entire depth to clear the field. To expedite this movement and allow more water to move, the slope is increased to 0.5% steeper than the slope of the infield for native soil root zones. Sand-based fields may instead decrease outfield slope to 0.25%.

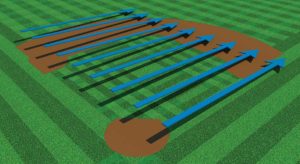

Sheet flow design

1% to 2%: Only native soil root zone ballfields at the recreational and sometimes high school level

Many fields, especially in the parks and recreation sector, are built on gently sloping land. It is very expensive to level up these fields so a conical drainage pattern can be used. Fields like this typically slope from one side of the field to the other. In this situation, a sheet flow drainage pattern would facilitate a consistent slope across the field to efficiently move the water along. The volume of water requiring drainage across the entire field surface makes this the least efficient method of surface draining. Because of the large volume of water moved, a steeper slope is a must to keep water moving. A system of French drains installed into the turf will facilitate the draining. Install them perpendicular to the flow to catch and remove water as it moves across the field. This will allow your builder to reduce the amount of slope needed. When sheet flow drainage is needed with your field design, be sure the field is aligned so that water does not run toward home plate. The field should be turned so that the home plate area is located on the higher side. Ideally, water flow would run outward toward the outfield. For sheet flow, the infield portion may be set at a shallower slope than the rest of the field.

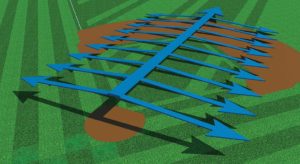

Split sheet flow design

0.5%: Sand based fields, all levels

1%: Native soil fields, all levels

This is a more effective surface grade design than sheet flow. It involves running a crowned slope down the centerline of the field (home plate to second base to centerfield). The home plate area is the highest point with a slope toward second base. In some cases, this centerline crown can be a flat crown from home plate to center. In addition to the centerline, the field is also sloped from out toward the right field and left field foul areas. This home-to-center and left-to-right pattern is why it’s called “split sheet flow.” This is commonly used on football and soccer fields, and was frequently used in professional baseball in the days prior to sand-based fields when multi-sport stadiums were common in the last century. This is still a reliable way to surface drain ballfields, and, unlike sheet flow, does not make the water travel the entire length of the ballfield. It is graded using a dual slope laser so the operator can set an X and Y axis to create two slopes perpendicular to each other.

The Ballfield Design & Dimensions Guide, Fourth Edition, presented by Beacon Athletics and DuraEdge, provides the information needed to design, construct or renovate ballfields. This expanded version features 56 pages of information about multi-field layouts, setting base anchors for new 18-inch bases, installing your infield skin, artificial vs. natural mounds, and more. For more information, visit https://beaconathletics.com/store/field-maintenance/field-marking-layout/ballfield-guide/