By John Kmitta

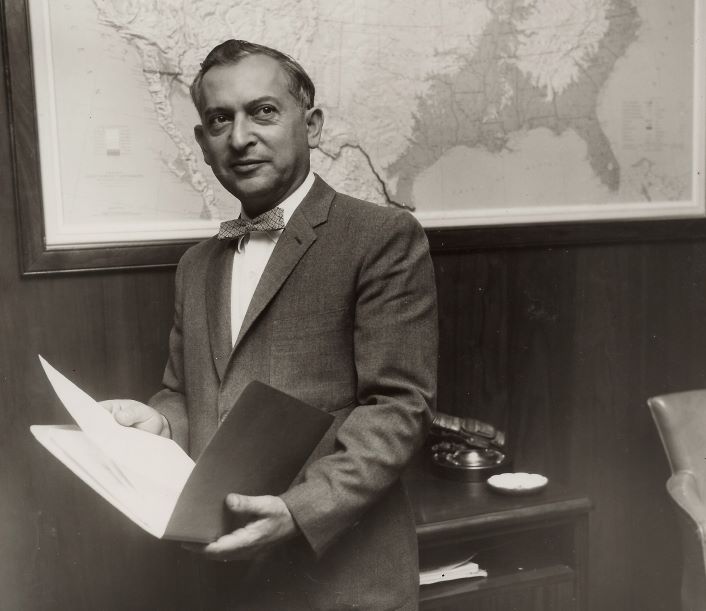

Inventor. Innovator. Salesman. Educator. Industry advocate. All of these terms can be used to describe turfgrass industry pioneer Tom Mascaro.

Born near Philadelphia in 1915 to parents who had immigrated from Italy, Mascaro contracted polio at a young age, paralyzing his entire left side. He slowly regained mobility everywhere except his left leg.

Mascaro’s parents couldn’t afford expensive treatments or procedures. But when Tom was a teenager, they were able to get him into a program at a Temple University hospital that conducted free operations as a way of teaching students in the gallery. Doctors were able to connect tendons and muscle from the front of Tom’s leg to those in the back of his leg. The doctors advised exercise as a follow-up to his surgery, so Tom began taking on jobs involving manual labor and physical activities.

Tom’s father was involved in the mushroom business at the time. When the Great Depression hit, however, nobody could afford mushrooms, and Tom, who had heard that golf courses used spent mushroom soil for topdressing, went to work shoveling and delivering loads of mushroom soil to golf courses.

“During the Depression, banks closed down and nobody had access to cash. However, when he delivered his first load of mushroom soil to a golf course, he received $50 cash,” said Tom’s son John Mascaro, president of Turf-Tec International. “He figured selling soil to golf courses was a pretty good business.”

Eventually mushroom soil became scarce as nobody was growing mushrooms during the Depression. Always innovative, Tom and his brother Tony found that a good way to make compost was to get leaves and mix them with soil and lime. They switched to selling composted topdressing, but were still challenged to get organic matter for the process.

“They decided to make a leaf rake that would rake leaves in large quantities. They gave one to the City of Philadelphia in exchange for their leaves, so that they could have free leaves to make composted soil,” said John.

The brothers, who had started their own company — West Point Products — met with Fred Grau, who was with the U.S. Department of Agriculture at the time. Grau was impressed with their leaf-raking machine and the brothers’ ability to innovate, but told the Mascaros that what he really needed was a piece of equipment that would tear up bluegrass fairways.

“When you tear up bluegrass fairways, it grows back better than it was before. Nobody is sure why; it just does,” said John. “They experimented with different ways to tear up bluegrass, and they came up with the Aerifier. It became an immediate success.”

The original Aerifier had no motor — it was just a unit that could be pulled behind a tractor on fairways and greens. Sports field managers soon found that it was a great way to cultivate the soil. West Point Products received the patent for the Aerifier in 1946 and the word was trademarked (the term has since become generic nomenclature). The Aerifier became such a success that the Mascaros abandoned the topdressing business and switched to producing equipment full time.

The success of West Point Products continued, as did their knack for innovation. In 1955, Tom Mascaro invented the Verti-Cut. Originally designed to vertically mow on a weekly basis, golf course superintendents and sports field managers quickly realized they could set the Verti-Cut low and verticut the dead material out of the greens and sports fields (the term verticut has also become generic terminology in the industry).

“During World War II, golf courses couldn’t get labor, fuel or even tires, so they stopped topdressing,” said John. “After the war, golf greens weren’t bad, so people assumed they didn’t need to topdress anymore. But over time, thatch developed and built up to thick layers on golf greens.”

When Tom went to sell a Verti-Cut to a golf course, he would have the golf pro putt across the green. Then Tom would Verti-Cut and let the pro putt again, and the ball would roll true as it eliminated ‘grain’ and reduced thatch.

“Golfers did not like the aerifier because it took the smooth surface on the putting green and made it rough for a time period,” said John. “The opposite was true with the Verti-Cut; golfers loved that invention.”

Tom – who held a Business degree from Lansdale School of Business, and had also studied organic chemistry at Temple University, inorganic chemistry at Drexel University and turf at Penn State University – was always thinking ahead.

For example, in 1968 he developed a battery-powered lawn mower for golf courses and home lawns. The product was a success at the National Hardware Show, and soon other companies were mimicking the concept.

West Point Products, which had grown to a thriving business with more than 100 employees, was eventually acquired as part of a hostile takeover, and later sold to Hahn Inc.

“After the company was sold, we moved to Florida in 1972,” said John. “He was retired for only a few months and started consulting with a sprinkler company called Safe-T-Lawn that developed some of the first home lawn pop-up sprinklers.”

In the mid-1970s, Tom invented a new product called Grass Cel, which was a golf cart path paving system made of plastic honeycombs that allowed people to drive over the soil without compacting it and still grow grass. With the success of Grass Cel, Tom started Turfgrass Products Corporation, which was the predecessor to Turf-Tec International.

John, who started to launch a t-shirt silk screening company after college, also began working with his father.

“He took me to the Florida Turfgrass Show, and I had no clue about the depth of this industry,” said John. “I thought it was really cool.”

John was also impressed by his father’s presence and impact in the industry.

“He knew many of the original founders of GCSAA and all the original founders of SFMA, current and past researchers, and I would just listen to all of these stories,” said John. “With his contacts I was able to make a lot of good friends and learn a lot about the industry.”

John started visiting golf courses and sports fields, and would take any new inventions to Dale Sandin at the Orange Bowl for testing.

“My father had made a slicing machine called the Verti-Groove with Dale to help drainage,” said John. “Dale was quite a critic; but every piece of equipment we had, I would go to the Orange Bowl, and we would try it out. I would then take it to golf courses and try to sell it out of the trunk of my car. The Penetrometer was one of the first things we invented. We had a moisture sensor, pH meter and thermometer, and we started leaning toward diagnostic tools.”

Tom and John Mascaro built Turf-Tec as a mail order company, with John typing labels on a typewriter and mailing flyers to golf courses and sports fields.

“We would get a check in the mail with the order form, and we would ship out the product,” said John.

John got to work with his father for 12 years, and together the two invented a wide range of products for the turfgrass industry. Tom Mascaro passed away in 1997.

“He loved making things,” John recalled. “Art was a hobby; he did clay sculpting, wire sculpting, and just liked to make things with his hands. As a kid, I used to hang around and watch him sculpt or repair things. He could repair or make anything. I learned a lot from him.”

According to John, many people don’t realize Tom’s contributions to the industry. For example, at early turfgrass conferences in the 1940s, Tom would carry a wire recorder, record the proceedings, have the information transcribed and turned into a booklet and then send it to all conference attendees free of charge. His goal was always to educate and advance the profession.

During his career, Tom taught turfgrass courses; lectured at approximately 20 turfgrass conferences per year for more than 50 years; served as an adjunct professor at Florida International University, Biscayne College and Nova Scotia Agricultural College; authored technical articles; developed a turfgrass correspondence course and a handbook for sports field managers and wrote a textbook tiltled “Diagnostic Turfgrass Management for Golf Greens.”

Among his many awards and accolades, Tom Mascaro received the U.S. Golf Association Green Section Award, the Distinguished Service Award from GCSAA, multiple Texas Turfgrass Association Awards, the Pennsylvania Turfgrass Council Recognition Award, the Oklahoma Turfgrass Research Foundation Award, Florida Golf Course Superintendents Association award for Lifetime Service, induction into the Oklahoma Turfgrass Hall of Fame and the STMA Lifetime Achievement Award. The Mascaro-Steiniger Turfgrass Museum at Penn State University was also named in his honor (and that of another industry pioneer — golf course superintendent Eb Steiniger).

Said John, “His creative mind was amazing. His inventions were way ahead of their time.”

John Kmitta is associate publisher and editorial brand director of SportsField Management magazine.