By John C. Fech and Brad Jakubowski

We all know that fertilizer is needed to establish and maintain high-quality sports fields. What may be in question are some of the specifics, such as which nutrients are needed, how much to apply, and when to apply them. These considerations are especially important in 2022, with shortages being experienced and prices on the rise.

Soil test

Don’t guess…soil test! We’ve seen this phrase on bumper stickers, calendars and signs on a trade show floor – and for good reason. If you don’t know what’s in the soil in which your turf roots are growing, how can you figure out what should be added to produce healthy turf?

Take a first look, then drill down. When reading a soil test report, look first at a handful of parameters:

- pH – pH influences the availability of essential nutrients, so if it’s out of the desired range, deficiencies are likely.

- Phosphorous – Essential for root growth and establishment of new turf.

- Potassium – Enhances overall stress tolerance.

- Cation Exchange Capacity – Indicates the relative capacity of the soil to absorb and release nutrients.

- Iron – The most common micronutrient to be in short supply and produces a light-colored, stunted plant.

If all the above are in good shape, then drill down for other readings that may be problematic.

Seasonal applications

Timing is important when fertilizing sports fields, and much of the emphasis should be placed on the field’s ability to absorb nutrients efficiently without adverse effects. It’s incumbent on the sports field manager to apply the essential nutrients at the proper time and amount to meet the needs of the field(s) without causing damage to the environment. With this in mind, it’s important to know (1) how each fertilizer carrier releases nutrients, (2) where to place your applications for best effect and (3) when to apply nutrients for greatest efficiency.

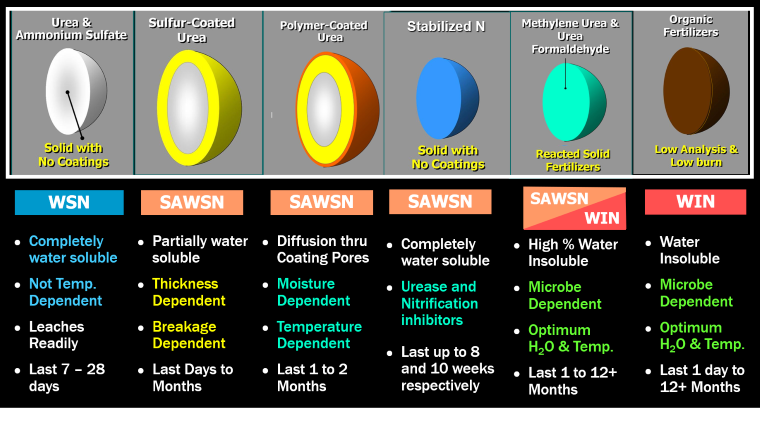

Figure 1 (above) provides specifics on the various release characteristics of fertilizer carriers found in common products on the market today. Most commonly, the nutrient in question is nitrogen. There are two general types of release rates for fertilizers: quick-release and slow- or controlled-release.

Quick-release fertilizers are primarily water-soluble nitrogen (WSN), and when applied to the soil and irrigated, will begin to release nutrients to the plant almost immediately. Slow-release fertilizers have a more complex make-up and a wider variety of formulations. The most common forms are slowly available water-soluble nitrogen (SAWSN). Of the SAWSN, sulfur coated urea (SCU), polymer coated urea (PCU), polymer coated sulfur coated urea (PCSCU) and methylene urea (MU) are most common. Other formulations are given the name water-insoluble nitrogen sources (WIN) and include urea-formaldehyde (UF) and a variety of organic sources. These sources are extremely stable and require ideal conditions to release nutrients.

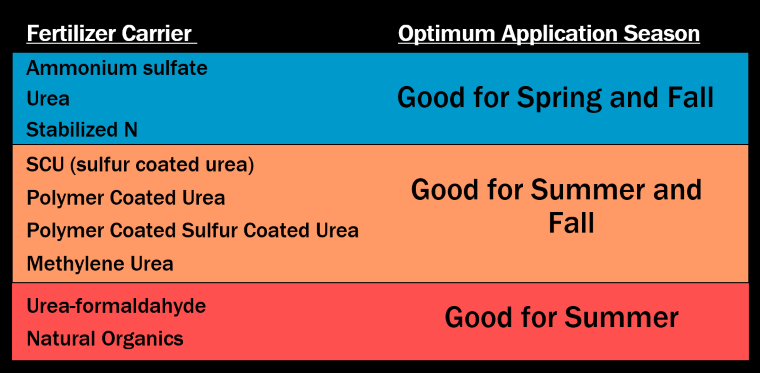

Because ammonium sulfate and urea are completely water soluble, they can be applied while conditions are cool/cold and unsuitable for microbial activity. WSN are the best choices during early spring and late fall. SCU, PCU and PCSCU are prills of quick-release urea coated with layers of sulfur and/or polymer to slow the breakdown of the fertilizer and the subsequent release of the nutrient. The rate of release depends on the thickness of the coating, soil temperature and moisture content. Stabilized N sources (i.e., LSN or UFLEXX) rely on nitrification inhibitors to delay the N conversion to nitrate, helping it stay attached to the soil as ammonium for a longer period of time. They are water soluble, but can be moderately applied throughout the season. MU and UF are homogenous fertilizers made up of chains of urea and formaldehyde reacted together to control the release of nitrogen. Generally, the longer the chains, the longer the release. Reacted fertilizers require water and microbes to break down the fertilizer, and are most effective when temperatures are consistently above 55°F.

Figure 2 illustrates the best times of year for applying the various types of nutrient carriers. Fortunately, many fertilizers are formulated with multiple carriers. This allows a sports field manager to reduce the number of applications that may be required during the season. For example, a fertilizer formulated with 25% urea and 75% methylene urea could potentially be used to apply 2 pounds of N per 1,000 sq. ft. in the spring and provide 0.5 pounds of N immediately and 1.5 pounds of N throughout the summer – all with one single application. This approach would provide an opportunity to reduce the need for several applications.

A big benefit from fertilizing in fall is to bolster turfgrass recovery from the numerous stresses of summer. Other benefits include increased winter stress tolerance, potential to expand the root system without a corresponding surge in foliar growth commonly seen in spring or early summer (that may occur at the expense of increased rooting), and reduced leaf succulence. Slow-release forms of nitrogen such as SCU, PCU and PCSCU that are activated via soil moisture are appropriate for early fall applications, as well as the microbially dependent MU, UF and organic sources. In late fall, soil temperatures are too cold for these sources to be of benefit; in this timeframe, a shift to quickly available soluble sources – such as urea, ammonium nitrate and ammonium sulfate – is best.

Figure 3 illustrates the incorrect application of a quality fertilizer carrier. This photo, taken November 7 in the northeast, shows two major problems. The first is that the fertilizer was not removed from an impervious surface and will be easily transported off site and lost (and likely lead to surface water pollution). The second problem is that the fertilizer applied is a methylene urea source. These require summer-like conditions to release the nutrient.

Cool-season and warm-season turf adjustments

Cool-season turf

With cool-season turfs such as Kentucky bluegrass, perennial ryegrass and tall fescue, good timing signals from Mother Nature are when the heat of the summer is over, yet while nutrients are still likely to be absorbed. As such, early fall and late fall are good timing targets. Early fall applications stimulate both foliar growth and root growth, but less foliar growth than an equal amount of applied product would encourage in spring. Photosynthate produced in late fall are not abundantly translocated to shoots, but instead move to stolons, rhizomes and roots in large part, helping the plants gain winter hardiness and earlier spring green-up.

In general, late-season programs do not eliminate the need for spring/summer fertilization, but allow the sports field manager the opportunity to use lighter rates that result in uniform shoot and root growth. The rate is also a key element in success of fall fertilization. In early fall applications, rates of 0.5 to 0.75 pounds N/1,000 sq. ft. encourage recovery and overall turfgrass health, while light rates in the 0.2 to 0.3 pound N/1,000 sq. ft. range are best in late fall when uptake is lower. In early fall, adequate time, temperature and moisture exists to encourage breakdown and utilization of the nutrients slowly and steadily, as opposed to late fall, when the goal is to get the nutrients into the plants fast and reap the benefits quickly.

If applications of K are needed, fall may not be the best time to deploy the nutrient in cool-season grasses. Potassium fertilization may increase snow mold severity, so K should be provided earlier in the season, which has the added benefit of potentially reducing anthracnose severity.

Often, summer is the offseason for cool-season turfs. When that is the case, lighter applications (0.5 pound of N per 1,000 sq. ft. per summer) of controlled-release sources are preferred to avoid overstimulating the turf and to reduce the risk of diseases. When managing summer-active athletic complexes (baseball, softball, soccer, etc.), 1 pound N per 1,000 sq. ft. of a controlled-release source applied at the beginning of the season is recommended. If the grass looks a little hungry later, light applications (0.25 to 0.5 pound of N per 1,000 sq. ft.) of a quick-release source can be applied. For intensely used areas, a divot mix that includes one part sand or soil, one part grass seed, and one part organic fertilizer source should be utilized in three steps: lightly scarify the areas prior to application, then apply the divot mix liberally, then press it into the field.

Warm-season turf

As summer gives way to fall, a traditional approach with warm-season turfs, such as bermudagrass, has been to reduce the frequency and intensity of the N applications in an effort to glide into late fall/early winter without much in the way of hearty plant growth that is likely to be damaged with ensuing cold temperatures. It’s difficult to argue with this tried-and-true methodology; however, research at several land-grant universities has indicated that light applications of soluble nitrogen in mid fall produce enhanced fall and spring color of bermudagrass turf without increasing the potential for winterkill.

In light of these discoveries, the application of low to moderate rates (0.2 to 0.4 pound N/1,000 sq. ft.) of quick-release N approximately two to three weeks before the onset of dormancy will provide needed nutrients for root and rhizome growth without stimulating excessive foliar growth. The lower, more quickly available formulations are in keeping with the questioning of the eventual fate of the nitrogen previously recommended, in either the slowly or quickly available forms. The basic question is if a large amount was applied in the fall, and a small amount was recovered in the spring, then what happened to the remainder? Really, only two possibilities exist: Either (A) it was used by the plant, or (B) it left the turf and moved to the atmosphere or leached to groundwater (both are undesirable outcomes). The balance with this approach is applying just enough that will be immediately utilized in the plant, but not more than is needed, as it is likely to be wasted or lost from the site.

Summer fertilizer strategies diverge depending on whether you are managing warm-season or cool-season grasses. For warm-season fields, the rule-of-thumb is to apply 1 pound N per month per growing season. Because warm-season grasses respond well to fertility during this season, regular applications of urea or ammonium nitrate are most cost effective. When possible, it is important to irrigate urea applications within a couple of days to reduce N losses to volatilization. Another option is to apply a single rate of 4 to 6 pounds per 1,000 sq. ft. of a controlled-release product such as methylene urea. This approach is most appropriate for non-irrigated warm-season fields.

Follow-up protocol

After any fertilizer application has been made, it’s important to wash the product off the blades and into the thatch. A light irrigation is sufficient. This is recommended for two reasons. First, removing the fertilizer pellets from the leaf blades greatly reduces the chances of foliar burn. Second, the thatch layer will act as a temporary binding agent, which will reduce the potential for off-site movement.

[Note: If plant growth regulators (PGRs) are being used, there is still a need to apply fertilizers to maintain a consistent food supply for the turf. Unless the PGR is running out of steam and the plant is about to come out of regulation, there will not be explosive growth with the grasses. Turfgrass density will be improved with the combination of fertilizer and PGR.]All in all, it is important to know what the field soils have to provide, then determine which nutrients are most critical to supplement, then determine the best carrier(s) and the optimum time to apply each.

John C. Fech is a horticulturist with the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and certified arborist with the International Society of Arboriculture. The author of two books and more than 400 popular and trade journal articles, he focuses his time on teaching effective landscape maintenance techniques, water conservation, diagnosing turf and ornamental problems, and encouraging effective bilingual communication in the green industry.

Brad Jakubowski is a turfgrass and irrigation instructor with Penn State University. He is a certified irrigation technician with the Irrigation Association and is an author and presenter covering multiple management areas within the turfgrass industry. He focuses his time on teaching best irrigation practices and troubleshooting, weather-based management decisions, soils and plant nutrition.

****************

Quick Guide: Timing

When to:

- Fertilize when turf is actively growing.

- Fertilize when turf is establishing – seed, sod, sprigs, plugs.

- Fertilize to assist with turf recovery after stress periods and heavy traffic.

When not to:

- Avoid fertilization when turf is surging due to microbial nutrient release.

- Avoid fertilization on the “shoulders” of the growing season – as the turf is going into dormancy and before the onset of growth.

- Avoid fertilization when turf root growth has stopped due to ultra-high temperatures – nutrient apps during this time may burn heat-compromised roots.