By Doug Brede, PhD

A December 2014 article in the Capital Press, a West Coast Ag newspaper, indicated that the Scotts-Miracle Gro company had gained federal deregulation of Roundup Ready turf tall fescue, with similar innovations in Kentucky bluegrass and St. Augustinegrass not far behind. This means they are free to plant and market genetically modified (GM) turf crops without further federal regulation. Genetically modified crops are commonplace in most Ag production fields. But this marks the first time GM has entered the turfgrass realm.

This article is a review of some of the pros and cons involved with GM turf. It’s a good time to examine this new technology before sales get underway.

Why the turfgrass sod industry needs GM turf

All industries commoditize over time. New industries initially spring to life by an innovation. Old-timers will remember when Merion bluegrass, Meyer zoysia, or Raleigh St. Augustine hit the market. Turfgrass producers couldn’t grow them fast enough. Raleigh was the subject of a whole episode of Fox’s King of the Hill. Meyer was featured on the Arthur Godfrey show. And, well, Merion was everywhere.

Consumers were buying on features rather than price. Later, as time went by and competitors entered the market, competition soon centered on price instead of features. That’s commoditization.

As a turfgrass breeder, I have seen some remarkable advances in our lifetimes in turfgrass genetics; all of these changes brought about by conventional cross-pollination and not laboratory methods. But I think our industry is ready for a quantum change that will put us back in the days of Merion or Raleigh in terms of product features. Those are the kind of changes offered by GM turf.

Roundup resistance is only a building block. You are probably wondering why the first GM turf product to make it to market is for Roundup resistance. If you think about it, that does seem odd. We already have a plethora of herbicides to control most any weed that comes in our path. Even homeowners have a goodly number of choices at the local box store. What does Roundup resistance bring to the table?

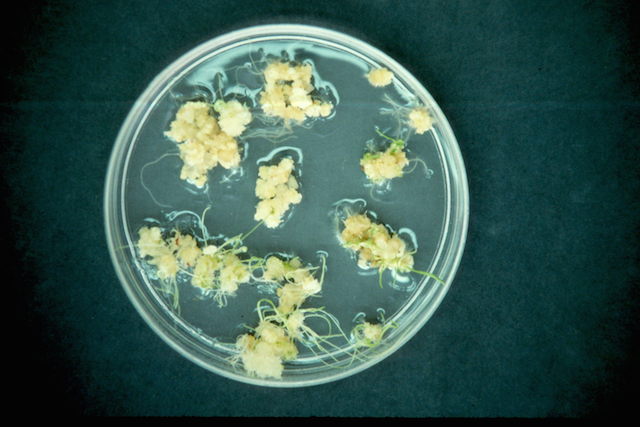

Roundup resistance is a “platform” that biotech scientists use to create GM varieties. When lab scientists insert genes into plant cells, they have no idea which cells are taking up the genes and which are not. If they’re lucky, 1% of plant cells will be transformed with the new genes. But how do you pick out those lucky 1% from the 99% that are unmodified? Simple, if you add a gene for Roundup resistance. Spraying Roundup herbicide on the resulting plantlets easily kills off the 99% that did not absorb the new genes. This makes it easy for biotechnologists to spot the transformed plants in the lab. They refer to this clever trick as a selectable marker.

All of the major agronomic crops (corn, soybean, cotton, alfalfa, canola, sugarbeet, etc.) all started out with Roundup resistance as their basic platform. Later they “stacked” additional genes on with the Roundup gene to add features to new varieties. Today, corn and soybean production in the US is greater than 90% GM.

So, yes, Roundup resistance is indeed a residual from the laboratory. But I believe we can turn it into a selling feature.

Spraying any herbicide increases the chance of creating herbicide-resistant weeds. Roundup is not unique in this regard. Any time we reuse an herbicide multiple times, we ‘up’ the chances of creating resistant weeds. With Roundup-resistant turf, we are not required to spray Roundup each time we need to kill a weed. You can always switch back and forth to 2,4-D to knock out any dandelions or weeds that may have become tolerant of Roundup.

Keep in mind that there are weeds that are already naturally Roundup-resistant. Clover is a good example. Also, common bermudagrass can tolerate a quart per acre with only superficial discoloration.

Cornfields will not be overrun by escaping GM turfgrass. When was the last time you saw lawngrass escape from your farm and overtake a neighbor’s Ag production field? Maybe if you were growing kudzu. But turfgrass? Seriously?

GM turfgrass is no different in this regard than conventional grass. Genetic modification does not endow it with super powers to escape and populate nature. There are selective and nonselective herbicides that can be used to control the occasional plant that makes it over the fence.

Federal oversight needs to change

By some estimates it costs north of $20 million to put one single GM variety through federal regulatory approval. While all this oversight does prevent the occasional mad scientist from releasing an evil product, it does inadvertently create a monopoly for giants like Monsanto. Startup companies don’t have the financing to get federal approval.

With turfgrasses it’s even more costly. In a cornfield you have a single variety of corn growing. In a turf field you might have five varieties of various species in the mix. If you intend to spray Roundup on that mixture, the seed inventor would have to put five varieties through federal registration, at the expense of $100 million. (Hmmm… I wonder if they offer volume discounts?)

So how did Scotts afford it? How did they get Roundup-resistant turf approved without breaking the bank? Unbeknownst to many, no federal agency has ever been created by legislation to approve GM plants. This authority was bootlegged from existing programs based on the fact that some pathogenic organisms and virus genes are used in the creation of GM plants. These federal agencies do indeed have the authority to regulate transport of potential pathogens or parts thereof.

But in a stroke of near genius, scientists at the Scotts Company created Roundup-resistant grass using no pathogens or viruses. Therefore their innovation does not fall under federal jurisdiction. I understand from a Scotts’ scientist that they are voluntarily putting it through some of the same regulatory paces, just for safety’s sake.

Arguments against GM turf

Opposition to GM turf is expected to come from both the far left and far right, politically. The only difference is whether they believe scientists are tinkering with nature or tinkering with God’s creation. And possibly (though not probably) you might find both sides uniting to picket your farm for growing unnatural grass.

One fact in favor of those who want GM turf is that no one “eats” our product. People are very touchy about what goes into their mouths. But they may give a pass to GM turf because no one eats their lawn. Or do they? When grass seed is cleaned, it is common practice to sell the chaff to feedlots. Even this simple consideration would require years of animal testing for safety, and would likely face suspicion from people whose cat or dog occasionally grazes on their lawn.

Other possible drawbacks of GM turf:

- Roundup resistance isn’t bulletproof: During certain times of the year when the plant is exporting into its roots it can become susceptible to damage from Roundup.

- Pollen escape: Although most turfgrasses don’t creep very far vegetatively, they can take a ride on the wind when pollen is shed. Scotts found out this the hard way when pollen from Roundup Ready bentgrass wafted 15 miles to cross with other bents in the landscape, creating Roundup-resistant weeds.

- Value proposition: Can I make money on this product? Do my customers really want Roundup Ready fescue? Are they willing to pay extra for this trait? Will the cost of the seed be cheap enough to allow me to make a profit? Will it create more problems than it solves?

Lesson learned from Roundup Ready bentgrass. Back in 2001, Scotts was introducing their new miracle invention to the golf world: Roundup Ready bentgrass. Like a bull in a china closet, they appeared poised to corner the golf grass seed market. From a business standpoint, this may have been the right course to take. But it made them no friends and several powerful enemies. The opponents dogged Scotts every step of the way, until finally GM turf hit a brick wall when the Fish & Game department gave thumbs down. Turns out, they didn’t want to switch herbicides for weed cleanup.

This time, Scotts appears to have learned a lesson or two about diplomacy, and rather than go it alone, seems to be putting out feelers for others who want to participate in the benefits and risks of GM turf.

Recently retired, Doug Brede, PhD, served as research director for Jacklin Seed by Simplot for nearly 30 years. He is the author of Turfgrass Maintenance Reduction Handbook and more than 500 articles on turf maintenance. In the interest of full disclosure, Brede and Jacklin Seed are not involved in GM turf, although Simplot has a program that recently released the first GM potato.

This article originally appeared in an issue of Turfgrass Producers International’s Turf News, which is why it refers to “farms” a few times. Our thanks to TPI for allowing us to reprint it here.