By Marc Moran, CSFM

Many sports field managers would agree that working with coaches and administrators can be similar to trying to solve a Rubik’s Cube. We often figure out one or two sides of that thing, while the others are left in chaos. Then we try to correct the chaotic sides only to realize we have messed up the sides we had already figured out. The pattern continues again and again. The reality of that comparison is that we keep trying. Just like with the Rubik’s Cube, we want success or some level of it.

In order to solve any problem or overcome any challenge, we first need to identify what makes it a problem or a challenge. Five common things that I believe create problems or challenges for most sports field managers are as follows:

1. Communication

One of the major challenges when it comes to working with coaches and administrators is the language barrier; you speak agronomy, they speak athletics. Often, you may have some experience in in speaking athletics, but are probably not fluent in the entire language. I personally can speak the various dialects of football, soccer, baseball and softball. As of this writing, I cannot speak lacrosse or field hockey. But I am trying to learn. Coaches and administrators often do not know the inner workings of agronomy, but they have you as a resource. The reality is that they will likely never learn it, but you have to do your best to translate what you know into a form they can somewhat understand.

Create a dialog about what goals coaches/administrators may have for a facility versus what your goals may be for that same facility. I know from personal experience that my goals for certain fields are often much different than those of the administration. So, at some point, it seems like we are pulling in different directions.

Take the time to communicate your ideas and goals with those administrators and coaches, and come to some sort of understanding as to which outcome is best. Sometimes the ability to compromise will offer gains for you far into the future. Be a part of the team.

Often, we become emotional when coaches/teams create undue damage on “our” fields, and we typically take it personal. It is important to take emotion out of the dynamic and use that opportunity to interact with a coach and take action through education. Be a teacher and explain what has happened and what steps could have been taken to avoid it and prevent it from happening again. Be genuine in your approach. Ask how their team is doing or recognize a big win or a tough loss in conversation before you discuss what challenges they may have presented you or your staff. Take a personal approach, learn their names, and treat them with a level of professionalism that you would want them to extend to you. We often miss that simple opportunity to build that easy connection and let them see you as a resource, not as a fussy ol’ groundskeeper.

2. Habits of coaches

All photos provided by Marc Moran, CSFM

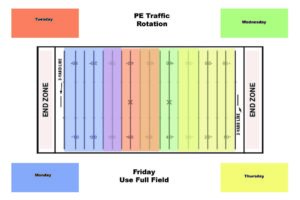

As you look at your interactions and communications with coaches, think of ways that you may be able to help reduce your challenges by proactively helping coaches break bad habits. We have all seen what happens when baseball coaches repeat the same dragging patterns on infields that they learned from their coaches who learned their coaches. After one or two seasons, you have huge infield lips and crazy hops. They come to you in a panic and want to know what you can do to fix it. You may want to say, “Step one is to get you off of the machine we use to drag the field!” But we all know that is not the approach or the effective answer. As stated, take that time to teach a coach a new technique. Coaches are used to evolving as coaches. That is why they attend coaching clinics and conferences. They seek more knowledge and new techniques to give their team an increased advantage in some phase of the game. Take that same approach when you look to help them improve their daily field work routines. I have grown as a sports field manager because I have taken the time to observe a few practices and games. I try to think of how I would set a drill up or run a similar practice, but from the mindset of a sports field manager. Do I need to paint a full field if only half is being used? Can I turn a field another direction at some point during the season? Do I need to paint a line if a cone will suffice? If you can share some ideas with coaches, and simply state, “I was watching your practice, and I was curious if it would help if I…” and slip your idea in there to them. In my experience, they rarely tell me no. Build the relationship based on helping them be successful.

3. Poor construction/facility design

Many of us have inherited problems from initial construction or poor design. Many times, we have been forced to live with them or find ways to work around them through innovation and ingenuity. Anyone who still manages a hydraulic irrigation system can attest to that. The best way overcome many of these facility challenges is to reach out to your fellow sports field managers or create industry partners who can give you good advice. If using an industry partner, make sure your athletic administration is invited in for the meeting or walk-around of your facility. If your administration hears what you are saying from an industry partner, they may be more likely to listen or look at the issue with higher level of urgency. At the same time, explain to them that having a person like yourself on new construction projects or renovation can often save them considerable money in the long term. Try to get a seat at the table whenever decisions about the facility for which you are responsible may be up for improvements or renovations.

4. Hands-on vs. hands-off coaches

Many of us have coaches who are totally hands off and basically show up, run practice and go home. If you are not prepared for that, then that can create a considerable amount of frustration – especially if you have been accustomed to a coaching staff that was very hands on. If you know the score in the beginning, it will often reduce your stress and frustration because you have the ability to plan and prepare for the work that you often counted on others to do. On the flip side, you may have very hands-on coaches who may need to be reined in a little because they become impulsive and quick to move on an idea when they may not have the complete picture. In the same light, you may learn something you never knew you would learn because a coach had an idea that you never thought about. I never would have suggested grass base paths for our baseball field, but my baseball coach in 2000 decided he wanted to do it and I can easily say it has been awesome.

5. Budgets

The last major obstacle is often budget. We never have enough and always want more. The reality, at least in a school setting, is that the purpose of the school is to teach, plain and simple. Athletic administrators are often reactive and make purchases because they have to make a purchase. They typically have about a dozen or so teams that each require funding at some level for uniforms and equipment.

They must pay for transportation and referees, as well as manage and staff games/contests. Throw the management of indoor and outdoor facilities into that as well, and that is a lot of pieces to a pre-determined pie. Through good planning and preparation, we can often give administrators a good idea of what we may need to be successful. We also need to make a list of “must have” and “like to have.” If the “like to have” gets kicked from the list, keep putting it on the list in the next funding cycle, find ways to fundraise for that item, or work with coaches to help slide that from “like to have” to “must have.”

When it comes down to it, one of the biggest things we can do for ourselves is to be effective communicators, innovative teachers and forever a professional. Use the resources that the STMA and its local chapters provide to help with education and innovation. Reach out to our peers to build relationships and seek advice. Be passionate and know that your role as a sports field manager affects the lives of the athletes who use your facility.

Marc Moran, CSFM, is turf science teacher at Atlee High School, Mechanicsville, Va.